| |

|

Some 225 miles from the routine clatter of New York’s evening commute, the men and women of Washington D.C. make their way home on a bitter winter evening. Much like New York, the nation’s capitol is home to a busy underground transit system: the WMATA. Like New York, the trains are often crowded. Like MTA patrons, D.C.’s commuters receive audio-cues to direct their actions in an attempt to maintain an ordered transit system. Like in New York, these cues consist of both live and automated announcements, as well as multi-toned electronic chimes (1/16/2015 WMATA Signal).

Recalling the “dou-dou-dou” of the Montréal STM subway system, and New York’s ubiquitous closing-door chimes, one can follow Giuffre and Sharp in identifying the WMATA’s tonal signal as a sonic anaphone. To quote musicologist Philip Tagg: “a sonic anaphone can be thought of as the musical stylization of sound that exists outside the discourse of music. Such sound can be produced by the human body, by animals or by elements and objects in the natural or man-made environment” (Tagg 2012, 487). The WMATA and the MTA both appropriate the language of music in order to construct simple and recognizable signals, and Goodman helps to articulate the affective power of repeated signals such as these. One simple definition of affect that Goodman offers is “the ability of one entity to change another from a distance” (Goodman 2010, 83). In a familiar scenario, the affect of music is often a change in the mood of a listener, or perhaps a compulsion to dance. However, Goodman might argue that in this current scenario the chimes’ affect is a minute sensation of fear to elicit a desired response (Goodman 2010, 69). The WMATA requires commuters to clear the area near the door before it closes. By de-contextualizing the familiar language of music, and employing repetition to establish its affective power, passengers are gently reminded to seek a safer position. While both New York and Washington D.C.’s subway systems employ such techniques, a striking difference is that in the WMATA this tiny affective sonic anaphone, appropriated from the language of music but not really a part of the musical discourse, is among the only music to be heard.

The lack of public performances in D.C.’s subway stations and aboard its trains is striking when heard by an earwitness accustomed to New York’s underground soundscape. The lack of music and other exhibitions is not the only sonic difference between the two subway systems. While trains still emit a variety of mechanical sounds, such as screeching breaks and hissing hydraulics, they come and go with far less sonic fanfare, comparatively gliding in and out of stations (1/16/2015 DC Metro Center PM 002). Exploring the train platforms of DC’s Metro Center, the atmosphere is subdued despite peak-ridership conditions. The comparative sonic order is partially attributable to the acoustic dampening panels that have been installed in the WMATA’s characteristic vaulted archways as seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6. January 16th, 2015. Pictured during AM peak hours at Union Station, the WMATA’s characteristic vaulted platform tunnels are equipped with sound dampening panels.

On a crowded train journey aboard the WMATA’s Red Line, the live public address is strikingly clear and intelligible in comparison to that typical of the MTA (1/16/2015 DC Union Station PM 001). A conductor politely addresses the commuters: “Once again everyone, thank you so much for boarding the train safely. Gallery Place/China Town, our next station.” As the train gets underway, several polite conversations can be heard in the car, which is impressively shielded from mechanical screeching and metal clatter. At each stop the conductor explains all relevant transfers, and is careful to remind passengers to mind their personal belongings and to be conscious of safety as they board and exit the train. The conductor politely asserts order at each station stop, and the earwitness is struck by the improbability of this conductor’s performance were he to attempt it in New York. Live announcers in New York are frequently difficult to understand over poor public address systems, particularly on crowded or rowdy trains, as is evident on this recording of a evening peak journey between Columbus Circle and Times Square aboard the MTA’s 1 Train (1/21/2015 Columbus Circle PM 008). Passengers easily obscure the grainy public address, and even mock the sometimes agitated conductor — and in a unique instance make an amused note of the earwitness’ recording equipment. Comparatively, the soundscape of the WMATA is home to infrastructure and cultural conventions that foster clarity of communication and a highly ordered transit experience.

It seems plausible that the WMATA’s careful attention to audio infrastructure and sound dampening may have habituated D.C.’s commuters to a less boisterous way of interacting with the subway’s soundscape. Looking to the Regulations Concerning the Use of WMATA Property, however, one finds a system of strict sonic behavioral regulations that portray deep institutional sonic phobias. Washington D.C.’s transit authority only permits “Free Speech Activities” in the “free-area - ‘above ground’ of metro stations” (WMATA [3] 2015, 11). Musical and artistic performances, political engagement, and religious as well as social speech are prohibited underground, and can only take place “at a distance “greater than 15 feet from any escalator, stairwell, faregate, mezzanine gate, kiosk or fare card machine. In no instance are any free speech activities to take place in the paid or platform areas of the station...” (WMATA [3] 2015, 11). The WMATA operates under the institutional ethos that paying customers should not in any way be subject to the sonic whims of the public at large, prioritizing peace and order over personal expression.

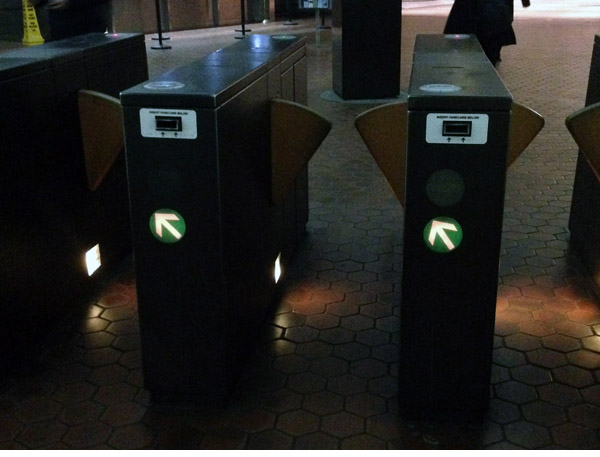

In addition to the impermissibility of underground musical performances, political and religious petitioning, and other behaviors that might fall under the heading of the strict moratorium on free speech activities, the WMATA has taken a simple infrastructural precaution to minimize the sonic impact that individuals and crowds have upon the subway soundscape by utilizing silent faregates. For comparison, we return to New York City. Unlike the robust cacophony that often characterizes New York’s evening commute, mornings on the MTA are often more subdued affairs. Musical performances are rare, and conversation is limited as New Yorkers struggle to find their feet each morning on the way to work. Nonetheless, each commuter becomes a momentary sonic actor as he or she swipes a MetroCard for admittance to the subway, triggering a characteristically shrill tonal beep and click to signal their correct fare, allowing them to push their way through a loudly cranking metal turnstile (1/8/2015 Penn ACE AM 001). In this recording from a morning commute at Penn Station most sounds are institutional; rumbling trains, station announcements, and the distorted voice of a station agent speaking to customers through a microphone, shielded behind glass. Though saying little, a mass of humans becomes an audible river of beep-click-crank, repeated again and again, each report announcing an individual commuter without the need for them to utter a single word.

In Washington D.C. the turnstiles are replaced by near-silent gates that mechanically open in front of each admitted commuter, as seen in Figure 7. When the commuter touches his or her fare card to the gate’s tap-and-go receiver, there is no programmed auditory signal. In this recording from D.C.’s Union station, a quiet mechanical sound is evident as the automatic gates open to the passengers, but is only audible within a small acoustic arena (1/16/2015 DC Metro Center PM 005). Perhaps this system is preferable. Allowing for each individual commuter to sound their arrival to the station might be considered an unnecessary burden upon the soundscape of a busy transit system. It is no surprise in Washington D.C., where “free speech activities” are forbidden both in underground facilities and aboard trains, that the transit authority prefers not to cede the character of the soundscape to a variable as uncontrollable as the number of passengers that happen to be passing through an entrance at any given moment. In omitting a gate signal, perhaps the WMATA has made a sensible acoustic design decision. Here we must return to Schafer, an idealistic champion of acoustic design, to understand the WMATA’s acoustic decision.

Figure 7. January 16th, 2015. Entry gates at Washington D.C.’s Metro Center subway station operate far more quietly than the turnstiles typical of New York’s MTA.

As previously stated, Schafer bemoans the relationship of modern design and architecture to sound and soundmaking. In 2014, the WMATA Subway was awarded the prestigious Twenty Five Year Award by the American Institute of Architects (AIA), which recognizes substantial architectural achievements in order “to establish a standard of excellence against which all architects can measure performance, and to inform the public expectations for architectural practice, its breadth, and its value” (AIA [1] 2015). Among the notable achievements recognized by the AIA were the visually iconic vaulted archways which “provide a place for sound-dampening panels” (AIA [2] 2015). Sound dampening is the AIA’s only mention of the WMATA Subway’s acoustic Properties, and Schafer’s notion is confirmed as he states: “the study of sound enters the modern architecture school only as sound reduction, isolation and absorption” (Schafer 1997, 222). This ethos of sound reduction is built into the architecture, infrastructure, behavioral regulations, and ultimately the audible culture of Washington D.C.’s subway system. An extreme contrast is drawn to New York’s MTA, which comparatively values public expression, be it social, political, religious, or artistic, perhaps to the detriment of sonic order and control. Implicit in this comparison might be the character of the cities themselves; one the seat of a sprawling centralized federal bureaucracy, idealizing efficiency and orderly conduct, and the other a world famous cultural center and a destination for artists, musicians, actors, and performers of all stripes.

|